Books

Memoir of a Non-Irish Non-Jew, 99 pages (paperback $999,999.99) by Richard May

What is our identity, if we awaken in the moment?

Memoir of a non-Irish non-Jew isn't about being Irish and Jewish or non-Irish and non-Jewish. It is about the chase of tracking down one's ancestral origins, whatever they may be, and the delightfully quirky unexpected discoveries that await you along the way, no matter what your family origins. "You are a link in the chain of your blood. Be proud of it, it is an honor to be this link," G. I. Gurdjieff. But it's also about learning not to identify with the achievements and failing of one's ancestors or even with one's own carefully crafted persona. "What do I have in common with the Jews? I don't even have anything in common with myself, " Franz Kafka. Who are we? Remembering with awareness of various levels of irony the response of Bodhidharma, the Indian monk who brought Buddhism from India to China, to King Wu's question, "Who are you?" — "I don't know"! What is our identity, if we awaken in the moment from the stories of our lives and the dreams of our culture?

http://www.lulu.com/content/803771

Paradise Emporium -- a collection, 247 pages - $9.48

by CL Frost

This newly released collection by a versatile, highly

skilled writer and artist includes short stories in the science

fiction, fantasy, magical realism and speculative genres. Among

these is the short story from which the collection derives its

title as well as many fine poems and a huge assortment of visual

artistry that also covers a wide variety of genres.

http://www.lulu.com/browse/book_view.php?fCID=561988

World of Villages: A Six-Year Journey Through Africa and Asia,

499 pages - out of print, but used copies are

readily available at very reasonable prices.

by Brian Schwartz.

The author traveled with, and stayed among, the native villagers

everywhere he traveled throughout Africa, Asia, and Indonesia

getting to know the strange behaviors of strange peoples.

Published in 1986 by Random House ISBN: 0517558157

Also published as Travels Through the Third World by

Macmillan ISBN: 0283992123

Brian Schwartz also wrote China Off the Beaten Track

- How to do it on your

own, published by St. Martin's Press ©1983 Library of

Congress # 82-61428. Copies of this book are also readily

available.

Aberrations of Relativity, 201 pages - $15.00

by Fred Vaughan

This is a collection of articles that emphasize one the most observable

aspects of relative motion, i. e., aberration effects. There are many

informative diagrams and illustrations with many new insights. What the

author calls "observational relativity" is defined in this book as a

possible alternative to Einstein's special theory.

The reader will gain valuable insights into all aspects of relativity

including why Einstein considered it necessary to embrace time dilation

and length contraction in his special theory, and why that might very

well not have been necessary.

The book is written for the intelligent (maybe very intelligent) layman,

with little in the way of advanced mathematics required to fully

comprehend the discussions.

http://www.lulu.com/content/572819

In Proust's Footsteps, 99 pages (hardcover $22.40)

by Maria Claudia Faverio

"In Proust's Footsteps" is Maria's fifth poetry book after "Entropy",

"Behind the Mask", "Metaphors instead of Formulas", and her "Selected

Poems" collection. Maria is a committed, award-winning poet whose books

are highly recommended by the Poetic Genius Society. Maria is also the

current editor for poetry and prose of the International Society for

Philosophical Enquiry.

http://www.lulu.com/content/430375

Learn about this talented Australian author, poet, and artist as well as her many creations of prose, poetry, classical music CDs, puzzle books, fairy tales, and artistic images at the following site: http://www.lulu.com/mycreations.

NATAN, 108 pages - $13.69

by Albert Frank and Muriel Hustin

Nath is a genius, Tanguy an idiot. Any such extremes disturb people. In

recognition of this fact, a pharmaceutical corporation is undertaking

experiment with a new drug, ?normality pills?, that would move them both

toward the norm. It is decided to put them in contact using e-mail

exchanges. Those responsible for the experiment will monitor the

exchanges. So a deep friendship evolves between two individuals who

normally would never have even met. Their dialogue is moving right up to

the terrifying conclusion. One of the themes of the narrative is the

loneliness of the extremes.

http://www.lulu.com/content/71060

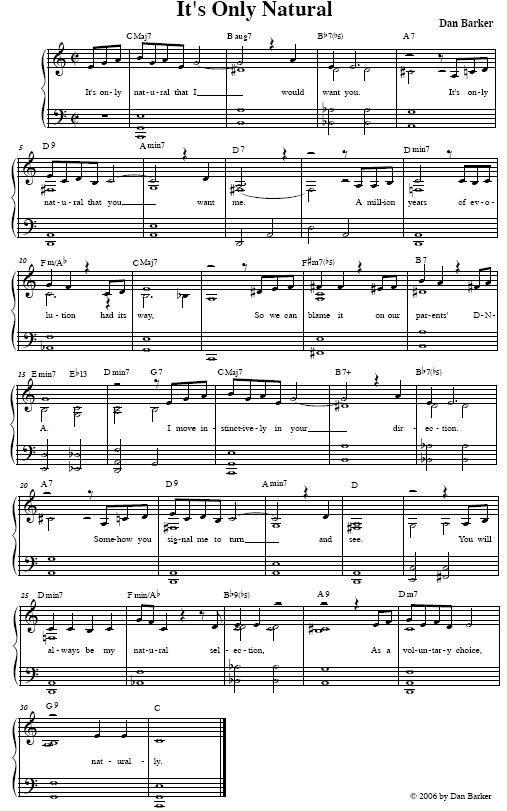

Losing Faith in Faith: From Preacher To Atheist, 342 pages - $25.00

by Dan Barker

After 19 years of evangelical preaching, missionizing, evangelism and

Christian songwriting, Dan Barker "threw out the bathwater and

discovered there is no baby there." Barker describes the intellectual

and psychological struggle required to move from fundamentalism to

freethought. Sections on biblical morality, the historicity of Jesus,

bible contradictions, the unbelievable resurrection, and much more. This

book is an arsenal for skeptics and a direct challenge to believers.

http://ffrf.org/shop/books/details.php?cat=fbooks&ID=FB5

The Magic of Ed Rehmus, 192 pages - $15.00

by Ed Rehmus (edited by Fred Vaughan)

This collection of creations by Edward Rehmus includes essays, artwork,

poetry, linguistic studies, comics, and puzzles. The style of Ed

Rehmus' prose is reminiscent of H. L. Mencken in his hay day. As a

friend said of Ed in eulogy, "He went for the bones of what he was

considering and the stormy winds could make off with the sails if that

was a consequence!" On his own behalf Ed had said, "What indolence and

what prodigality to trust to usage that which ought always to be

spontaneous, creative and conscious: speech!"

http://www.lulu.com/content/476575 - regular price.