Mnemonics can be defined as "a technique of

improving the efficiency of the

memory". It sometimes means "a system to develop or improve the

memory",

implying a specific set of routines to achieve this

improvement, but the first and wider definition is the one used

here.

The goal of this article is to briefly describe what mnemonic

techniques are and a few ideas regarding how they might be used

when playing chess blindfolded. The research has consisted of

articles and e-mail exchanges with the very competent blindfold

player Hindemburg Melao Jr.

Footnotes are used exclusively to indicate sources or

cross-references; a chess player is referred to as "he". Thanks

to Andreas Gunnarsson, Eliot Hearst and Hindemburg Melao Jr.

What is mnemonics?

The memory processes

Memory if often divided into four major processes, and I will use

these categories to help explain my view of what mnemonics are.

Attention and selection — what you

notice; you choose (consciously and/or unconsciously) what to

focus on.

Encoding — what you have chosen to

focus on is changed, encoded, into the things to be

remembered.

Storage — how you hold on to the

information; some memories fade faster, others slower.

Retrieval — recalling what you have

previously stored.

Some mnemonic guidelines you know from your common sense. For

example: with regards to attention you need to focus. When it

comes to encoding you need to keep it as simple as possible. What

is the most effective way of storing (visually, audially,

kinesthetically, etc.) differs somewhat between persons. The

variant you use spontaneously is probably a good clue. Retrieval

depends not only on how well the memory is stored, but also on

what you have to do to remind yourself of it (for example,

sometimes you forget why you walked into the kitchen, but you

know that you can do the walk over again and it will probably

come back to you).

Mnemonics builds on this and lets you be more efficient in how

you use your memory. It is basically just a continuation of the

common sense, taken to a level many people do not bother with

because they normally do not need it in their everyday life. It

is all built on principles natural to us, simply because these

are the ones we do best.

The role of mnemonics in the different memory processes

To improve the attention and

selection process you can practice concentration, both

intensity and stamina (some form of meditation is often used to

achieve this).

In this process we also include everything that has to

do with creating an environment suitable for concentration. This

includes external factors such as avoiding any disturbances and

being given new information in a way that is clear and that you

are comfortable with. It also includes internal factors such as

being in good health, rested, relaxed and without any feeling of

(negative) stress or pressure. In this process is also something

seldom mentioned: the question of what you are supposed to pay

attention to. The reason this is so rarely included in any

mnemonic guides is of course that it is very subject

specific.

Just to be clear: mnemonics means the deliberate use of ways to

improve these factors. We can all concentrate more or less and

what we do without having to actually think about it is not

included in mnemonics. It is true that continuous use of mnemonic

techniques will incorporate these into your normal thinking.

However, when that happens, they are no longer mnemonics.

The encoding process is where you

find all the famous mnemonic tricks that make up so much of the

self-help literature on this

subject.

So how can we make this process as effective as

possible? We start by making the information we must remember as

simple and logical as possible.

By organizing the information we lessen the amount to be

remembered. We do this by distilling from our sources what we

actually have to remember, we look for patterns and we decide how

much of what we have left that actually has to be memorized. Not

all of the original information needs to be encoded, you just

need enough to remind you. Once you have found the memorized

cues, you can often take it from there and remember the rest. So

how do we encode what we have left?

Because we are different, the methods most effective to us differ

as well. But there are still some general principles that seem to

apply to practically everyone. One of those is that it is easier

to imagine something concrete. A concept or anything else

abstract is transferred into something concrete, which is

remembered (concrete means you are able to sense it; see it, hear

it, smell it...). In this and the other encoding situations

imagination plays a big part.

Another basic concept is that it is always easier to remember

something that has a clear connection to something you already

know. Association with something familiar gives you a specific

place to put the new stuff, a place where it is easy to find

later. In order to make the associations as rich and effectual as

possible, it helps to use all senses. Not just see an image but

think about what it sounds like or what it smells like, or

anything you might imagine. It is also good to attach some form

of emotion or mood (if that doesn't come by itself); an emotional

event is easier to remember than one you don't really care about.

A note about automatic encoding (also called "chunking"): In

practically all aspects of life we use what is called implicit

knowledge to automate tasks we perform regularly. For example,

you do not have to think about how to walk, how to talk or how to

read. It comes automatically. As mentioned above, this kind of

simplification of input is not included in the term mnemonics.

Storage itself is not subject to

mnemonic techniques, but the result of the other

processes.

The retrieval is, because it is the

decoding process, inevitably linked to the encoding process.

Whatever you have associated with the memorized information is

your key, so that is what you use in finding it again. If there

is still something you cannot remember, the only thing you can do

is search for it.

If you have something "on the tip of your tongue", that is if you

know you have the information but cannot access it, you can in a

limited way still look for cues. If it is a specific word, like a

name, you can look for it by trying to start the word with the

letters of the alphabet, one by one. Hopefully you will be

reminded while trying the correct letter.

This sort of retrieval help, which is really

just a form of systematic search, is only the last resort and not

very effective. When developing the mnemonic techniques, all the

work goes into the attention and selection and

encoding process (in other words the input

processes).

How can mnemonics be utilized in blindfold chess?

Remembering one board

Some parts of mnemonics are always present, no matter if you use

a specific system or not. They are the ones in the

attention/selection process. You have to be focused and you have

to pay attention to only the game. All the factors regarding

focus and concentration mentioned above apply.

In the encoding process the simplifying of information is always

there, mostly spontaneously. This is what has been called

"chunking" of information. This is necessary if you are to handle

all the information needed to play a chess game, but since it is

automatic, it is not included in mnemonics. (It is possible to

focus on this part of the process while playing, but that

counteracts itself since the goal is to have less to focus on,

not more.)

Chess players don't remember a position piece by piece, as a

non-chess player would be forced to. They see relationships

between squares, pieces, pawn structures, open files, and so on.

The better the player, the more efficient the chunking of the

information of what the board looks like, and the more elaborate

the associations of squares, pieces and piece configurations. For

someone who doesn't play much chess, playing blindfolded sounds

like an enormous mnemonic effort, but it is much simpler for

someone who has the tools for it. Being a good player means

having an efficient set of tools.

When it comes down to it, remembering the game, as in remembering

all the moves in their correct order, is not the same thing as

being able to "take in" more or less the entire board at once.

This kind of comprehension is required because it is the only

thing you have to go on to calculate your next move; just

remembering what piece moved where is not enough. If you have

enough knowledge and skill at playing the game with a board that

you can plan moves without it, then remembering what you did is

not a problem. It is then not much information to remember. This

means that playing blindfolded is not really a question of having

a good memory, is it about being able to comprehend the position

enough to be able to plan your next move. In a way all players

use this ability more or less even when they have a board in

front of them; while planning ahead, they envision pieces moving

and watch for what kind of position the moves lead to.

In blindfold playing, there is a skill

level below which the information gets too complicated for the

brain to process. Master blindfold player Reuben Fine (1914-93)

has written he believed that knight odds level is required to

play one game blindfolded, while master level is necessary to

play more than one game

.

As people differ in there working memory capacity, the

required level probably correlates with both size and

configuration of that capacity, as well as with ability to

concentrate. Examining this and getting more information about at

what level of chess skill blindfold playing is possible would

make interesting research but I have found no more information

than the above cited article.

There have been suggestions how to remember

chess games even if you are not a competent player. Dominic

O'Brian has suggested using a variant of the Journey

method.

He gives the different pieces personalities and the

Knight so becomes Sir Lancelot of the round table, the Queen is

Elisabeth II etc. Then algebraic notation itself is made able to

visualize. Each square is turned into initials by changing the

number into a letter, c3 becomes CC (represented in his example

by Charlie Chaplin) and f6 FS (Frank Sinatra). The different

images are then associated with each other and stationed along

the mnemonic itinerary. This way of memorizing results only in

recollection of moves in their correct order. It does not relay

any relationships between pieces, which means that no matter how

many games you remember, it will not improve your

playing.

We come to the conclusion that some general parts of mnemonics,

more specifically the ones you can benefit from in any type of

situation, help if you want to play blindfolded. More specific

tools, such as the systems found in many books, do not.

Remembering more than one board

Let us assume a person can play one blindfold game of chess. How

can he go about if he wants to play more than one game

simultaneously?

Playing more than one board could be seen as doing the exact same

thing as with a single board, but with the amount of information

to be remembered multiplied with the number of boards played. It

could also be seen as two different and separate activities,

playing (comprehending) one board and remembering the others.

In the first alternative the skill level required must be

significantly higher than when playing only one board. In the

second alternative, the player uses the same way of playing the

single board as he has done when playing only one game. The

factor added is to put the other board or boards aside and recall

it for the next move; that is, simply remembering something

enough to be able to recall it later. I say "simply" because this

process does not require this board to be available to plan moves

or strategies, it just has to be stored. The issue of being able

to use the board for planning moves is still only needed for one

board at a time. The other boards are stored, ready to be picked

up again and played, and this storing is the area of the type of

mnemonics featured in popular mnemonic systems (a number of which

are listed in the Appendix). In reality, however, you will not

find anyone using exclusively one of these two alternatives. They

represent only the extremes of a spectrum.

The more you use a mnemonic technique, the more automatic it

gets. You simply get better at doing it as you chunk the steps

involved better and better and eventually it gets fully

automated. A good example of an automated process is the way you

read. You probably do not have to think about what the letters or

even the words mean, as you were once forced to. But it is not as

simple as that, and rechunking happens many times during the

learning process. What is to be chunked changes as comprehension

of it improves, and comprehension improves when the new chunks

are organized. I will not try to explain these developments, but

I will look at where mnemonics can be applied.

When you recall something you start with one detail and that

detail reminds you of another, and then another, and soon you

have more or less the complete memory. And even if some detail is

missing you can probably find more than one path of association

to remind you of it once the others are in place. Accepting this

model of our memory we get two places where mnemonics can do

their thing: helping us find the first clue, the "key," and

helping associate the pieces of information so that the key will

lead to all the rest.

The associations between the information involved in a chess

position are always more or less spontaneous, since the moves

follow a specific plan and this binds them together. The best way

to help a player to improve is probably just to remind him of the

basic guidelines of mnemonic associations and let him do the

specifics (I say this because personally adapted mnemonics are

always the best, and I am careful not to try to improve on the

spontaneous by applying a general model). The guidelines,

described briefly in the first part of this article, are: use

your imagination, look for patterns, use all your senses,

associate with something familiar, use concrete images. All these

rules apply also when remembering the key bit of information, but

as this is a more straightforward memorizing, mnemonics can here

be given a larger and more elaborate role. For this, one can use

any of the systems described in a number of books on mnemonics

and memory.

Making the boards distinct

The most common problem described in simultaneous playing is that

of mixing up the boards. If you only play two boards then this

will not be a problem since you will be working on one of them at

any given point in time. But how do you keep the boards separated

when playing ten boards or more? By making them different.

A common technique is using different

openings to separate boards. When playing twelve games, the

blindfold player use one opening on four of the games, another

one the next four and play black on the last four (or some

similar system).

Some people think that the memory used by blindfold

players is built up by a memory bank of "normal" positions. This,

they conclude, would make the game easier to remember if it did

not include any unexpected strategy or odd moves. If they try

these in order to make the player forget the game easier, the

effect becomes the opposite: that game is immediately singled out

from the others and thus easier to

remember.

In this way it is a matter of time before games become distinct

enough from each other that there is no chance of mixing them up.

The problem is the player must at all times have the

distinctiveness of the games clear enough, even if only one or

two pieces separate them. This kind of situation not only lends

itself to mnemonic systems but to a particular type of system

called "loci". Loci means place and the system consists basically

of positioning that to be remembered in different surroundings

already familiar to you. In your mind you already know your way

around many locations, separate not only in space and time but

also with regards to the feelings you associate with them; these

locations can be used when profiling boards. The way the locis

are used must depend on how the game is already comprehended and

remembered by each player, but here are just a few suggestions:

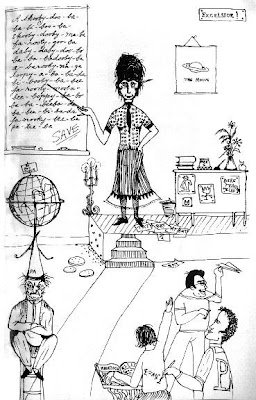

If the game resembles a normal game in the way it is envisioned,

why not play one game at your kitchen table, one at your favorite

chess club, one in the park. Use familiar places and odd places,

even imaginary places. If your view of the game is more of a

story unfolding then let it play out before you on different

stages. There are no rules when it comes to this and weirder is

often better. Another way to approach it is to imagine familiar

historical personalities as opponents, why not Napoleon or Sun

Tzu (author of "The Art of War").

I am unfortunately not a good enough chess

player to test these ideas in practise so their utility is so far

not much more than a guess. However, some prominent blindfold

players have been able to perform tricks worthy of any mnemonic

expert,

so there are very likely already quite a few productive

ways to use these systems. My humble suggestions above will of

course not work for everyone, but my hope is that it will help

someone.

Appendix - Common mnemonic systems

Below are a list of the most popular mnemonic systems. It is easy

to see that many of these are variations on the same themes and

they often overlap. There are many good books describing these

and the way they can be used. The names used are the most common

according to the many sources I have checked when compiling this

list.

Link — you link together each thing to

be remembered in an often-absurd story.

Substitute word or phrase (also called

Keyword) - if the thing to be remembered is not easily visualized

you substitute it for something else.

Number/rhyme (Pegword) — use something

that rhymes with the number, for example 1 = bun, 2 = shoe. This

is then used to get a numbered list by associating a shoe with

something you know is item number two on a list.

Number/shape — instead of using

something that rhymes you use something that looks similar to the

number. 1 becomes a stick or a candle, 2 becomes a swan

etc.

Major (Figure Alphabet, Phonetic

Alphabet) — each number is represented with one or more

consonant sounds. 1 = d or t, 2 = n, 3 = m, 4 = r. The number

43214 becomes for example "reminder" (r-m-n-d-r).

Alphabet — some image is connected to

each letter instead of number, usually representing something

that starts with that letter. A = ape, B = Bee, C = Sea

etc.

Loci — the images to be remembered is

placed in a certain location (= loci). For this you use a real

building or route you are familiar with, either real or imagined.

When memorizing or recalling you imagine walking the same

route.

Journey — an extended loci system that

often includes travelling between known locis. Sometimes denotes

the same system as loci.

Roman room — once again thing placed

in a location, usually a room, this time not in any specific

order.

Footnotes

by Richard May

by Richard May