"Bob", Will declared sternly,

"You perform well in front of the camera. But

every time I see you back-stage, you're

pacing, biting your nails, and moaning about

something."

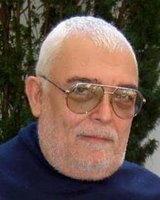

"Yeah. Sure. I know." As one of the station's two leading

weathermen, Bob had to seem part wizard, part scientist, part

seasoned outdoor explorer; his TV public expected him to brave

the elements wielding a gilded barometer and squinting through

jewel studded binoculars at omens scrawled in mist across the

underbellies of clouds. After so many years on the job, he could

don his costume, hunch his back, pull his brow into a concerned

omniscient frown, and intone his lines automatically; recently,

however, he'd spent too much time grumbling to Will, his

weatherman partner.

"I know all about our history," Bob rubbed his palm

repetitively up and down the armrest; underneath, the fabric

shimmered, scuffed smooth, shiny and pale. Bunch of

incompetents!, the public had shouted in protest against

weathermen: All that fancy equipment, they'd do as well with

divining rods and crystal balls! Where'd they get their science

training? Sue them! No, shoot the frauds! If they're gonna pull a

fast one on us, they should pay! "I know how

they used to treat us. You're right. We have it good. I should

just say my lines and forget. I should remember that these are

good times, remember to forget."

Bob scratched spasmodically at his uncombed, slightly matted

beard as stiff and gray as a brillo pad. Ever since his

grandmother's death a month earlier,

he'd felt more and more irritable; he

remembered too much. Whenever he glanced at the regulation

polyurethane container in which her ashes were sealed, his

stomach twitched in rebellion; he felt like vomiting up

everything he'd eaten and heard during the

last twenty-five years. When he tried to sleep, his heart beat

out thunderous warnings and the muscles in his legs writhed,

trying to squeeze out invisible toxins; something primordial

pounded at his skull and hammered in the dark emptiness behind

his eyes. He told himself that he was merely grieving for his

grandmother, the only person who'd excited his

imagination in a world scrubbed clean of spontaneity. He reminded

himself that his grandmother and her stories had come from an

archaic time, best forgotten, before scientific regulation had

freed the world from fear and inconvenient surprises.

Before scientists had learned to control the weather, people

expected perfect predictions from their meteorologists. If the

forecast read "blizzard", people stockpiled groceries and Aspirin

for the backaches that followed shoveling; if the forecast read

"sunny", people anticipated feeling happy. When drivers,

surprised by an ice storm, crashed their cars, everyone blamed

the weathermen. After an unforeseen tornado toppled the main

street of a mid-western capitol, multi-million dollar settlements

didn't calm the public outrage; the assassin of a meteorologist

was pardoned on the grounds of justifiable homicide. After a

hurricane veered abruptly off course, crashing historic landmarks

and burying a coastal city under toxic silt, members of the

underground organization Cloudsmart bombed hundreds of weather

stations. The time had come for science to tame nature.

Now, rain fell only between midnight and 6 AM. No more than a

half-inch of snow, guaranteed to melt in hours, ever fell.

Occasionally, the government staged a midday thunderstorm or a

blizzard "just like in the good ole days" to stimulate the

citizens with a show of environmental novelty; the people were

warned a week in advance. Children read about tornadoes and tidal

waves in history books and marveled at the hardships endured by

primitive society.

Bob had gleaned his own knowledge about the weather of ancient

times from history books, reprinted photographs, old videos, and

tales told by his grandmother, who'd lived through subzero chills

and soil parching heat during childhood. As Bob dressed for his

show, where he and Will would tell the nation what sort of

weather the government had planned for its citizens, he thought

of Grandmother's mementoes, a lifetime of

accumulated photos, letters, e-mail print-outs and news clippings

saved in musty boxes now stacked in Bob's

apartment. Since her death, he'd spent hours

daily examining the artifacts of her life, squinting at yellowed

scrawl and faded type on paper dried to parchment brittleness and

studying the figures in tea-stained photographs speckled with

basement mold.

One photo, of his grandmother as a young woman with head thrown

back, drinking rain through her open mouth while shimmering

silver curtains poured from her outstretched arms, stood out; Bob

had tacked it centrally above his bed.

"For a while, I wanted to be a

storm-chaser, wanted to woo nature," Grandmother had

told him. "I was a child of the

elements."

In the hot, moist wind, I'd stand outside among the thrashing

trees, abandoning myself to the power and willfulness of the air.

Bob knew the story by heart, recounted and embellished in so many

of Grandma's electronic letters. When I went

storm-dancing, I wore a long wide skirt that whipped in the gusts

until welts rose on my legs. I drank in the energy of the frantic

electrified air, the rain surging down like an angry mob. I was

the Storm Dervish, whirling wild and fast as a twister down the

water-polished streets as the rain drummed, thunder clanged, and

the wind sang soprano death-scene arias. Damned if I was going to

carry a purse when I went storm dancing; I spent a night in the

town jail when the cops found me, spinning down a deserted street

while lightning lashed the sky, without ID and unable to prove

that I wasn't high or crazy. That was my last storm dance - in

2002. I mourn that part of my life, but it's not something I

could do anymore, even if the weather still was a beast calling

to other beasts; one has to be young, free and fearless to

surrender to the poetry of wildness.

Will slid into his usual seat next to Bob. "Yeah, I'm glad I

didn't work in this field back then," He pulled a towel around

his shoulders, ready for the technician to apply his make-up.

"Nowadays, we don't have to worry about insane crowds. We don't

have to predict anything."

Bob winced. "Back then, we would have been doomed prophets. Now

we're just actors". His grandmother had known theatrical skies

and operatic winds. "But I wonder how it feels to experience

something more unexpected than a stubbed toe."

In this time when even nature had been cured of orneriness, news

anchors reported global peace, family harmony, affluence

throughout the nation, and empty prisons. According to one rumor,

however, the long peace was a fiction, invented after the

anti-war protests of 2032 had raged to near revolution; a few

reportedly had glimpsed secret footage of American infantry

charging into a charred jungle during an ongoing, decade-long

African war. Some speculated that the president was a holographic

image, and that a secret faceless group ruled the country; others

argued that the president avoided public appearances, preferring

videotaped speeches even during the campaign, due to a history of

frequent assassination attempts. TV reporters merely read from

teletype, never leaving the studio; journalists fleshed out

computer data sent from the official news bureau. Most people

clung to the hope that officials and experts wouldn't lie and

that they could trust in the continuing calmness of the world.

"Huh? What's that about stubbed toes?"

"Nothing," Bob grunted, as Tina, the make-up technician with

spiked fluorescent hair tugged his beard into place. Her

Jingle-Band bracelet tinkled a melody from one of the

day's top-ten hits whenever it slid up or down

her arm. At Tina's squawked command, the chair

hummed and angled Bob's face upward; Tina

draped a protective white bib over Bob's

costume, then muted her Jingle-Band bracelet so that they could

all hear the big television that murmured, bleated and squealed

above the make-up counter.

"Aren't you the lucky

one!" Tina's fingers fluttered

over cotton wads and jars of pigment; the stars etched into her

long nails glowed, screaming yellow and shrieking orange against

a shy pink background. "I

can't think of a better show to watch while

you're getting pampered.

It's my daughter's favorite

show, and mine, and my sister's, and even my

husband's; we all try to sneak a look, even if

that means telling the boss we're sick and

have to spend extra long in the ladies' room.

But you must know how it is, being a TV guy yourself. When

something extra-exciting's calling to you, how

can you say

"'no'?"

The dressing room's large set played

continuously, always showing the station's current broadcast.

Most other performers envied the weathermen. The program airing

just before their studio appearance ranked as television's most

popular; many said that Bob and Will, watching the

day's most exciting show from reclining chairs

while nimble fingers massaged pigment into their cheeks, were the

luckiest of men.

Trapped between the chair and Tina's roving

hands, Bob stared at the big screen.

"Welcome to Psycho-Moms From Hell!" On screen, the show's host

swaggered across the stage in his sequined jacket while horns

blasted to a crescendo in the background. "Which psycho-Moms will

make it into the pit? And which one will make it out, as a

challenger for the fifty-million-dollar prize? Remember, only one

of the chosen will survive to become the star. So, girls and

boys, tell the audience why your Moms are nuts enough for the

mega-million dollar Psycho-Mom of the Month award."

Bob gulped back the burning fluid that lurched up from his

stomach and seared his throat.

"My Mom dresses like a tramp," the first teenage girl squealed.

"She wears earrings that dangle all the way to her shoulder,

eight on each ear; you can hear her coming from a block away,

like she's wearing cow bells. She uses fluorescent orange eye

shadow. And when she walks through the mall, she lets one

tattooed breast hang out of her blouse, so all the passing guys

stare at the snakes feeding from her nipple. From the way she

dresses, you'd think she was my age"

Will snorted. "Hooters from Hell! All the tit

men wanting to grab a feel and not paying any attention to the

daugther - wanna bet the kid's just

jealous?"

"My Mom won't let Robo-Maid in her room to clean," the second

teenager batted large green eyes at the camera. "She says she

doesn't want anyone invading her privacy, even a machine. So her

clothes are all over the floor, stacked five feet high. She can't

even find the remote control in all that mess".

In the dressing room, Tina's hand hovered over

Bob's face, a moist tan sponge gripped between

thumb and forefinger. "I sure hope my

husband's watching this, him always calling me

a slob" she tittered. "What they

should do — what would be really exciting

— they should sell tickets to see these Nut

Cases up close and personal. Meet the belle of the bells, and

listen to her tinkle as we chase her. Or visit this

privacy-freak's nut house in Fruitcake City,

and watch her try to keep Robo-Maid from doing its job. You

couldn't stop my Robo-Maid from cleaning

unless you took a hammer to her instrument panel;

they're made to be persistent,

isn't that a fact?" Bob nodded and

shut his eyes, trying to recall his

grandmother's words and photos from that other

time.

"No, keep those eyes open, I need them big

and wide to get the shading and wrinkles just right,"

Tina clucked. Bob cleared his throat, gulped, and stared

obediently ahead. In front of him, on the glaring screen, the

show's host strutted to another fidgety

teenager.

"Purty crazy!" the announcer crooned. "And let's hear about Mom

number three"

"My Mom keeps hundreds of pet roaches." The girl spat a wad of

purple gum into a tissue and tossed back her blond hair. "She has

them all in little cages. They all have their own names; she's

even painted designs on some of their backs. The one called

'Sunflower', has a big acrylic sunflower painted on it; there's

'Lilac' and 'Violet' and 'Dandy Lion'; she swears they all have

different personalities. She's trying to train them to roll over,

and the meaner ones to do guard duty, attack a robber when she

shouts 'Sic him, Rover Roachy, sic him!' It wouldn't be so bad if

she didn't like to eat with her favorites; she coos to Sunflower

and Violet over a bowl of spaghetti, then claps when they perch

near her coffee cup and wave their antennae at her. I even wrote

a poem about it, you wanna hear?"

"Do we want to hear it?" the host asked the audience.

"Yes!," the audience cheered.

"Are we sure we want to hear it?"

"Yes, yes, yes!" the audience screamed.

"O.K., it' s called 'Roachy'," the girl cleared her throat as she

unfolded a piece of paper, "And goes:

Attach a leash to your roach,

Strut proudly in the lead.

When critics gawk and reproach,

Say "He's an exotic breed,

Sired specially and pedigreed",

Say "My roach is not an 'it' - a 'he',

And he's very cheap to feed.

So I pamper him with luxury -

A hotel where he and wife can breed."

"Purty crazy!" the host boomed. "So, audience, which will it be,

Mom number one, Mom number two or Mom number three? Will it be

the scamp of a tramp, the robo-phobe or wretched roachy?"

"Three! three! three!", the audience shouted.

"Who?", the host bellowed.

"Roachy! Roachy!" The audience chanted, clapped, and stomped its

feet.

In the adjacent chair, Will coughed. "For my

mother, a roach was Public Enemy Number One.

She'd have shot them if she owned a gun, but

she had to crush them; then she handed us kids paper towels and

ordered us to wipe up the pieces of shell and the oozing bug

juice. Didn't want to touch even the tip of a

roach leg - but that's normal."

Will snickered. "Those roaches must have

crawled into this lady's brain. Watching her

in the pit — you can't beat

that for excitement, can you?"

Bob grunted. "Manufactured

excitement," he sneered inwardly. When his

grandmother was young, the world had seemed like a capricious and

willful creature that frightened and exhilarated humans with the

whims of its weather and its politicians; people sometimes

trembled, but they knew that something unpredictable would jolt

them awake after a period of too much calm. Adrenaline junkies,

people needed a frequent adrenaline fix. Possibly, the need was

coded in our genes; in a world of constant, predictable calm,

people hungered for the unexpected;

yesterday's surprise no longer shocked them

awake and they needed the increasingly loud and putrid to arouse

their sleeping senses. "Today, when the wind

must call on schedule", he seethed,

"We create artificial excitement".

As Tina rubbed fragrant, calming oils into

Bob's neck, he squeezed his eyes shut against

the roiling images on screen. The applause of the studio audience

softened into the thrumming of ancient, wayward winds: The wind

pranced up a roof and somersaulted down. The field was its

trampoline and tree branches its jungle gym. It shook confetti

leaves loose; they spun up, then tumbled to ground, scribbling

the field with streaks of paintbox red and crayola yellow.

Grandma, pictured as a little girl in another snap shot, pranced

out in her little-girl shoes, to play tag with the cartwheeling

wind; she dashed to the crabapple tree, her very own juggle-ball

tree, with its thousand dangling round purple fruits that the

wind might have hurled into the forever-blue sky if only it

hadn't impulsively decided to play elsewhere.

Bob recalled that photo of a five year old Grandma, her dress

billowing and hair swirling, more vividly than he recalled any

moments from his own life.

"Come on, be a dear and open those gorgeous

eyes for me so I can do your face right," Tina cawed.

As she pried open his lids with her raucously painted talons,

Bob's gut writhed and his foot shook

spasmodically.

"Roachy, Roachy!" The shouts

stabbed Bob like surges of high voltage current.

"O.K., bring her out!" A squat, orange haired woman in a purple

caftan waddled forth. Her name and story had been submitted to

the networks months before; she'd already passed three screening

auditions testing that her personality, as well as her psychosis,

would excite viewers. She raised her plump fists victoriously

over her head, shook them in time to the chanting, then sat

grinning in the seat beside her daughter.

"O.K., Mizzz Ruthy Roachy, you're Psycho-Mom of the day; you've

won a chance in the pit." The host's voice deepened to a growl.

"But can you scratch, claw and beat your way out of the pit, to

that five-million dollar prize in the sky? Let's look at your

competition."

A gaunt face with lava hair and midnight-dark eyes scowled on

screen. The audience hissed.

"That's last week's champion Psycho-Mama, Ms. Mean of Green, mass

murderer of trees. She's got a vendetta against oaks, hacked down

a yard of 200 year old trees with a rusty axe, even though her

robo-gardener would take care of any pruning and raking; now her

yard's full of knee-high stumps. And when the government staged

that snowfall last winter, she tried to shovel it off her

driveway with a kitchen spatula, even though everyone knew the

white stuff would be melted in a day. She may look small but

she's tough; so far, she's beaten four Psycho-Moms into dust.

Ten-in-a-row and she's a megabucks, mucho moolah, millionaire

Mama, even if she quits and doesn't go for higher stakes. So,

Mizzz Ruthy Roachy, can you beat the Lean Meany of the Green to

the prize?"

"Roachy! Roachy!", the audience hollered.

"Roachy! Roachy!", Tina and the other make-up technician cheered.

Bob clenched the armrests with his fists until the straining

knuckles burned with the white of hot steel.

"What kind of a world is this?" he

spat into his beard, then clamped his lips shut.

On screen, spikes of neon-red hair stuck out from a crimson face;

the wide eyes, hot as embers, burned furiously. The audience

booed.

"That's Dame Dread of Red, who'll also meet you in the pit. Her

favorite colors are fire-engine red and black. When she moved

into her house, she bought a hundred gallons of paint; now the

walls and stairs are hot red, while the ceiling, carpet and

electrical outlets are black. She yanked out all the original

plumbing, installed a red tub and black toilet. She drives a red

car with black seats and only wears black dresses with red shoes.

She sits under a sun lamp all day, to keep a fiery burned

complexion; 'Better dead than not red', she tells dermatologists

when they warn her about skin cancer. Can you beat Red and Ready

in the psycho-pit?"

"Roachy! Roachy!", the audience screeched. "You can do it, go

Roachy!"

"You can do it!" Will cheered. "Go Roachy!"

"Roachy! Roachy!", the make-up technicians chanted.

Bob wiped the sweat from his neck with jerky staccato rubs as an

inner fire seared his skin. "What kind of a

world is this?" he growled. "What

kind of a world is so desperate for thrills?"

On television, the stocky woman rose from her chair, raised her

fists and flung back her head.

"I can do it! I'll scratch them till they bleed, punch them till

they drop, kick them when they're down and out till no more juice

is in them. I can do it; I'm Psycho-queen!"

The losers would die in the pit, beaten to death by the other

contestants; usually, the victorious Psycho-Mom emerged with

broken bones, bruised organs and scars, but famous, five million

dollars richer and a contender for the fifty-million dollar

prize.

The audience roared.

"Roachy! Roachy!" In homes and offices across the nation,

housewives and break-time employees cheered and booed. Tina

hissed, then hurled a moist sponge at the screen; the other

make-up specialist stomped her foot and chanted. Will bolted

upright, shaking his fists. Every face purpled; bulging neck

arteries throbbed, pulsing hot with anger or triumph as the

championed Psycho-Mom, who seemed more real than the

viewer's own biological mother, punched,

kicked and clawed for blood in the celebrity arena.

Bob, the only one still seated, gaped at the screen and gasped

for breath. Two women would die in the pit; one would emerge,

battered, rich, today's celebrity cheered for

the moments of excitement she'd given to a

dulled audience. Was this what happened when everyday life became

artificially predictable, routine and comfortable, sapped of any

suspense?

"You're on in three minutes, " an intercom voice bleated over the

buzzing commercials. Both weathermen reached for their floor

length capes of gold and silver, studded with rhinestone stars

and moons, and fastened these over cobalt blue shirts and

trousers. Each lifted a pearly wand from the stand.

Bob rubbed his wand carefully, then leaned against the door. "I

wish I could do something different tonight," he mumbled, staring

at the floor. "Like forecast a blizzard for tomorrow."

"A what?" Will glared at his companion. "You know that they've

planned sunshine for the next month. So why would you defy the

script? People would panic if they thought the weather wasn't

going according to plan. And what about tomorrow, when it's sunny

all day? You'd probably lose your job. Everything would be in

chaos. People wouldn't know whether or not to

trust the weather bureau."

Bob frowned, then sighed loudly. "Don't you ever get bored just

reading scripts the officials hand you? Don't you ever want a

little excitement, something unpredictable?"

"Maybe," Will protested. "But this is a good job. All we have to

do is wear these capes, read lines someone else writes, and look

serious, the way people imagine sorcerers would look. If I want

excitement, I can turn to Psycho Mom. But not in real life; I

don't want surprises in my real life."

"Showtime in sixty seconds,"

the intercom rasped.

The weathermen ambled down the corridor, each stroking his beard

to a point to resemble that worn by a fairy tale magician.

Suddenly, Bob stopped, beating his wand against the floor like a

cane. "I do! I want surprises. And maybe I'm

not the only one." He straightened his back until he seemed as

tall and indestructible as a lightning rod; the glittering tip of

his wizard's cap seemed ready to scratch the

sky. "People know that the weather's

government controlled. But, maybe, some of them still want to see

us as forecasters in a universe full of mystery. They want to

believe in the possibility of excitement. They want to

anticipate, want to wake up to more than programmed days of

comfortable monotony. Maybe they want to know that some can hear

divine music in a way unexplained by genetics and evolution; they

need prophets and the unpredictable."

"You were born centuries too

late," Will chuckled.

"Computers are always right; they're programmed to be." Bob

insisted. "If they're not,

there's something wrong with the software. You

know what distinguishes the prophet, or any human, from the

machine?" Bob stared past his partner, at something

encoded in the crystalline air. "He's

sometimes wrong."

Will shook his head. "A medieval monastery,

that's where you belong."

"Beauty and magic require randomness. And prophets have immense

power." Bob's dark eyes burned, embers

untouchably hot with passion, under his frosted false eyebrows.

"For evil, maybe," Will spat out.

"Could be, " Bob clutched his wand to his chest; his fist gleamed

like a tiny moon against the swirling nebulae stitched in his

cloak of flaming violet. "But I want to see what it's like to be

a prophet of gloom. Tomorrow there will be a

blizzard…."

by Sean J. Vaughan

by Sean J. Vaughan