When Mr. and Mrs. Jackson first read the ad, they shook their

gray heads in mutual disbelief.

"Too good to be true," Mr. Jackson croaked.

"The schemes these advertisers come up with," Mrs.

Jackson groaned. The newspaper shook in her hands as she moved it

to a distance from which she could read the tiny print through

her bifocals. "You have to admire their cleverness. Or maybe,

their audacity."

|

|

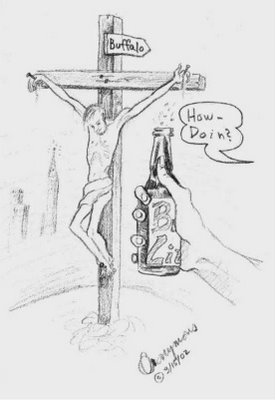

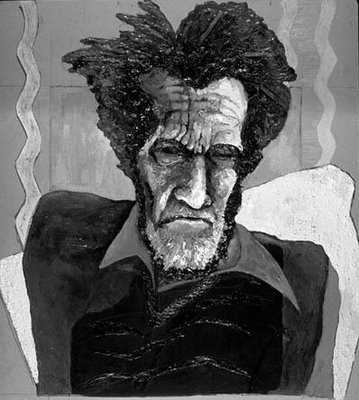

Image by C. L. Frost

|

|

Mr. Jackson nodded as he swallowed his morning pills

- a scored orange tablet, two green and white

capsules and a pale blue lozenge - with a

mouthful of decaffeinated, artificially sweetened coffee. The ad

reminded him of those he'd read inside matchbook covers and on

the back of comic books in his boyhood. It reminded Mrs. Jackson

of those Elixirs of Everything, secret formulas guaranteed to

cure heart-ache and aging, sold in the housekeeping magazines

that her mother had read for decades; newer magic potions, those

offered nowadays, added "lost medicines of the Incas" and

"remedies derived from recently discovered esoteric Hindu

teachings" to the concoction. She cleared the phlegm from her

throat and began to read:

"Deal of the Century! First annual Gray Sale, for senior citizens

only. Amazing discounts! Lazy-Boy loungers with kid leather

upholstery, only $25. Big screen TVs, only $30. Golf carts, only

$10. Do you live on a fixed income? Trouble affording that

computer you want to buy your grandson? That piano for your

granddaughter? New laptops only $50. Baby grands, and a year of

free music lessons, only $100. Want to help your daughter remodel

her kitchen? Refrigerators, all sizes and colors, just $50;

ranges only $40. Everything must go, all prices slashed. First

300 shoppers win a free Caribbean cruise, two weeks in January

aboard the Merit Fleet's premier luxury liner.

First 500 win a free hot tub, guaranteed to sooth aching joints.

Merchandise limited; come early before inventory's gone. Sale one

day only - Saturday, September 1st, 10 AM

- 8 PM at the Paradise Emporium on Rte 8 at

the Elmsbury fair grounds."

Mr. Jackson reached for the paper and squinted at the miniscule,

faint print that his wife couldn't see.

"Discounts are made possible by funding from the federal and

state governments," he read aloud. "Plus a long line of insurance

companies." He paused. "I wonder what the catch is."

"Some trick, for sure." Mrs. Jackson licked her parched lips and

sipped tea to wet her mouth before continuing. "We'll get in

there and find bargain basement clothes with designer labels

- look-alikes until you examine the seams,

which are already unraveling. Or big boxes of cereal that look

like they could feed an army, but with hardly enough inside to

fill a baby's breakfast bowl. If there's a

baby grand, it'll probably be made out of

plastic and small enough to fit in a dollhouse. The golf

cart'll have torn sides and rusty wheels

- dragged there straight from the city dump.

Probably another scam to fleece us old biddies.

Aren't we all dim witted? Isn't everyone with

wrinkles and bad knees senile? An easy mark?

Don't we all drool over our pudding, dribble

Ensure over our bibs and wear adult diapers?"

Mr. Jackson nodded as he placed a red check mark in the upper

left corner of the calendar box for Wednesday, to indicate that

he'd taken all his morning medications.

"And I never heard of altruistic insurance companies," he

muttered. "But, we have a few days until the sale; maybe enough

time to find out what really lies behind that ad."

When Mr. and Mrs. Jackson left the house to investigate, they

found that all the senior citizens were talking about the sale.

Maxine Stritch, the bony seventy-five year old neighbor who

lovingly weeded her garden daily despite her arthritis, seemed to

bounce on tip-toes; excitement had sucked the pain out of those

knobby joints. Anna Difrancesco, the baker's widow, gestured

enthusiastically; her plump but agile hands drew arabesques in

the air. Tom O'Toole, raconteur and retired electrician, spoke

faster and faster, until he began wheezing and perspiration

beaded on his reddening scalp.

"The Gray Sale? Of course I'm going!" exclaimed Maxine. "I'm

getting there early, 6 AM. Maybe 5 AM, with a fat pillow and a

blanket to camp out in front of the door. I want to be one of the

lucky three hundred, spend winter basking under the hot Bermuda

sun. And my grandchildren want their own computer, not just

scheduled time on their parents' machine; they

keep asking for one, but you know how much you can buy on a

school teacher's pension and social security. So, this is a

windfall - if I can beat the lines."

"It's the deal of the century!" Anna's large brown eyes sparkled

like those of a restless adolescent in love.

"Haven't you seen all the commercials? Every

fifteen minutes; they've been advertising for

weeks. Just one dollar gets you a raffle ticket for a Cadillac

- straight out of the factory, shiny new, any

color you want. And they're giving away two

hundred. Two hundred! Winners'll be announced

just before closing, and I'll be in there,

waiting; I'm driving out of there in a

sparkling new, hot pink Money-Mobile. Even if I

don't win

-" She paused to pat her

thick gray hair into place. "Everyone always

laughed at me for keeping Alfie's truck, the one he used for

delivering breads and cakes. 'What's a widow-lady going to do

with that big clunker?' they wanted to know. Well, come Saturday,

they won't be wondering any more. With everything selling cheaper

than week-old pumpernickel, I'll be pulling every credit card out

of my purse and thanking the gods for plastic money. Don't need

it this year? I might need it next year. Not sure if I can use

it? One of my kids or grandkids might use it, and like it for a

gift. No excuse not to buy, and that truck holds a lot of stuff.

If they sell big TVs and Lazy-Boy Loungers with suede cushions,

I'll be storing a new living room in there. Not a Junk-mobile

- now it's my

treasure-mobile."

"Of course it's real!" laughed Tom. "My son, the one in city

council, says they've been planning this for months. Most of the

nursing homes are renting vans to take their residents to the

event; some didn't want to at first - with all

the liability issues, what if Joe Nasty's Grandma gets trampled

by the crowds? - but the residents got too

excited when they heard about what was coming, demanded to go and

threatened to beat the administrators with their canes if they

were kept in. The big city's chartered special buses to drive us

golden oldies to the sale; the city papers have been advertising

Paradise Emporium for almost a year. Buses with fat velvet

cushions and seats that recline, for us oldsters with bad backs.

Pick-up at our own front door, if you so request. A nurse on

every bus, just in case. And other cities and towns, every one

that's less than a hundred miles from the fairgrounds, has plans

for transporting its seniors."

Tom paused to catch his breath and wipe the sweat from his shiny

pink scalp; then, grinning like an aging leprechaun, he inhaled

deeply.

"On September 1st," he mused, "Hundreds of buses, all filled with

grannies and grandpas wanting to shout a Hip-hip-Hooray camp

cheer, will speed down Route eight. Pity any policeman who dares

to stop one of those buses! The passengers might beat that cop

bloody with their walkers, strangle him with their Foley catheter

tubes, sting him with the insulin needles they carry concealed in

jacket pockets. Folks'll get feisty, even the sick ones;

don't keep us from the Mall-of-all-malls! And

can you imagine the evening headlines? 'Cop attacked by mob of

seniors, who behave just like teenage hooligans.' Might be the

start of a new movement; we might see laws describing canes and

catheters as lethal weapons."

That day and the next, Mr. and Mrs. Jackson toured the town,

speaking to old people whom they knew already and old people who

were strangers. They drove to the Senior Activity Center in the

long, wide Ford they'd bought during an era when they thought

they'd live forever; with many replaced parts, the lovingly

waxed, lemon-yellow car was almost as old as their marriage. They

entered Sam's Deli, favored by seniors because it was owned by

one capable man as old as themselves and staffed by family

members who knew every customer's name: while slicing cheese or

spreading lox across warm bagels, Sam would chat about politics

or the marital problems of a grandson who lived on the other

coast. They strolled into Tony's Foods, the last individually

owned grocery in an age of chain supermarkets filled with glaring

fluorescent light and clerks trained to smile robotically through

their indifference; at Tony's, the amber light softened craggy

profiles and treated old eyes gently, and the

proprietor's warm welcome made even an old

person feel that he was still human, not yet an invisible ghost.

Sam's Deli and Tony's Foods would be closed on Saturday; Sam,

Tony, and most of their patrons planned to spend the whole day at

Paradise Emporium. Sam even proposed making September 1st a

holiday, National Geriatric Day, to be celebrated with parades of

costumed marchers wearing masks of wrinkled faces with sagging

jowls and thin lips; the marchers might dance nimbly around

walkers and twirl canes like batons while high school bands with

off-key tubas played favorite old tunes.

"Ideally," Sam winked at Mrs. Jackson, "The band would play

perfectly. But, have you ever heard a high school band with all

the horns on key? Doesn't exist! So, we soothe our nerves,

jittery from all that bad playing, with gourmet feasts cooked

without salt and entirely with low cholesterol, antioxidant-rich

foods. Sorry, none of my prime Mozzarella on Old Age Day!"

Tony glanced at the personally stocked shelves in his store and

shrugged.

"I'd close the shop

anyway," he said as he fixed price labels to cans of

tomato soup. "Want to get Timmy that bike

he's been asking for all year;

they're selling ten-speeders for thirty bucks.

But who'd come here anyway, even if I kept the

place open? No one - not when

they're offering a free all-you-can-eat

lobster buffet at five, and a big band playing Glenn

Miller's greatest hits. Lobster! I

haven't tasted it in years; buying it is like

buying diamonds. So I'll be there all day,

mouth watering."

Early each evening, Mr. and Mrs. Jackson returned home exhausted

from their rounds of listening to old people enthuse about the

Sale-to-beat-all-Sales at the Paradise Emporium; no one asked why

the government and insurance companies would treat the elderly so

charitably. Mrs. Jackson called her friends from the Senior

Activity Center. Mr. Jackson called his poker buddies

- five limping, sometimes incontinent,

stiff-jointed but sharp-eyed men who formed his "circle of

curmudgeons".

"Everyone else is going," Mrs. Jackson said on Friday night, as

she ladled rice and peas onto her plate. "I usually don't like

crowds, but I wouldn't want to miss a great event."

Mr. Jackson placed a green check mark in the lower left corner of

the calendar's Friday box, indicating that he'd taken the scored

orange tablet, the crimson capsule, the two green and white

capsules and the huge tan pill prescribed for dinnertime; the tan

pill always scratched his throat, stuck in his esophagus and

squeezed into his stomach only after several gulps of water. He

added a check mark to the lower right corner, indicating that his

wife had also taken her evening medication.

"Jeff - the guy with the colostomy bag," he

began hoarsely, "Jeff's excited about the sale; he's going with

his sister, who's staying at his place overnight and drove six

hours to get to the event. Ned, the one with gout who sees

through my poker face every time and says that I'm too bad a liar

to ever play at real poker; penny poker's it for me, as high as

I'll go. Well, Ned thinks that the politicians recognize how many

people in this country are over 65; we're a big voting block, can

make or break a candidate. So, the politicians want to get on our

good side. 'Make nice to the seniors,' they say, 'If you want to

keep our seat in congress.' So, we're right to question the

motives behind this Paradise Emporium. They're not really giving

charity; they expect us to repay them at the ballot box. But,

that doesn't mean that we can't enjoy the spectacle and

capitalize on a few bargains."

Mrs. Jackson crushed a pea under her fork and watched the pulpy

green interior ooze up between the prongs.

"It's probably just my overly cautious nature that makes me

uneasy," she said, and reached for her teacup. "Maybe

I'm too skeptical, too conservative. Sometimes

you have to trust people and take risks to get the most out of

life."

"So true," Mr. Jackson mumbled, then swallowed his mouthful of

rice. "I had my doubts too. Big doubts. But if the curmudgeons

are eager? Some of those guys wouldn't trust a

little kid peddling Girl Scout cookies; they act as though

everyone's trying to sell them land on the moon. If they don't

sense anything wrong, neither should I. Any unease is just my

suspicious nature acting up." He cleared his throat and spoke

more loudly. "So, what time tomorrow do we leave for Paradise?"

Mrs. Jackson shrugged.

"Whenever," she sighed. "When we've finished breakfast, had our

warm showers and feel ready. No reason to get up early for the

mad rush; we need our sleep. Besides, where would we put a hot

tub?"

The next morning, after a breakfast of oatmeal and Ovaltine, Mr.

and Mrs. Jackson drove under a bright, high sun to the Elmsbury

fairgrounds. Yellow police tape and sawhorses blocked off roads.

Filled parking lots gleamed as metal reflected the white

sunlight; to Mrs. Jackson, the snugly aligned cars resembled

nesting beetles. A policeman stopped the yellow Ford and directed

the Jacksons to a lot three miles away; a shuttle bus drove them

back to the fairgrounds and deposited them at the end of the line

of people awaiting entry into Paradise Emporium.

"It's a tent!" Mrs. Jackson exclaimed when she saw

the white fabric arced between steel poles and rigging. "It looks

like a series of snowy mountains. And the line

- there must be five hundred people between

here and the entrance."

Mr. Jackson sighed as he considered the long wait ahead of him,

pulled a tube from his pocket, rolled up his trousers and rubbed

analgesic cream onto his knees. Alerted by the whiff of menthol,

Mrs. Jackson reached for the tube, then rubbed the ointment into

her lower back. A monitor in white trousers and a navy jacket

stitched with gold brocade on the cuffs and pockets, one of at

least fifty patrolling the grounds, sniffed, strode briskly to a

ramp, then rolled two plushly cushioned chairs towards the

newcomers.

"We want you to be comfortable,"

the monitor said as he patiently helped Mr. and Mrs. Jackson into

chairs. "No reason to strain those joints while

you wait."

A cheery hostess pushed her cart parallel with the line, stopped

before the Jacksons and offered to pour them glasses of cider,

bottled water, sugar-free lemonade, or iced tea.

"We also have finger sandwiches and three

kinds of soup, all cooked with low cholesterol products, if you

get hungry." The hostess, as slender and professional

as an airline attendant, smiled at the Jacksons.

"When the line moves forward, you can stand up

and push your chair; it has wheels. But if

you're tired, you can flip this switch and

activate the motor; you can navigate by pushing this lever, let

the chair roll you forward and do all the work. It

doesn't move very fast, so you

won't bump into anything. Besides, a

monitor's always watching; one of us will be

there if you look like you're going to hurt

yourself. If you need anything, if you need something to drink or

need to use one of our bathrooms, just push this big button. A

monitor will see the blinking lights on the sides of your chair

and come to help you. Any questions?"

Mrs. Jackson shook her head. Mr. Jackson activated the motor, let

the chair wheel him back a foot, then returned to his original

position; a light nudge moved the lever.

"I wouldn't mind having a

chair like this at home," he marveled as he sipped

spicy warm cider. "And if I turn this knob, the

bottom slides out and I get a foot-rest; I can keep turning to

raise and lower my legs. The people who organized this event

understand how old feet need to be propped up."

Mrs. Jackson let Seltzer water bubble over and clean her tongue.

Overhead, a lone cloud floated nonchalantly in the crayon-box

blue of one of late summer's perfect days.

Sunlight caressed her, warm but not hot; breezes cooled, but

didn't chill, her. An ambulance idled silently

fifty yards away, medical care available for anyone who needed

it. The door of one of the many Porta-potties opened and a

uniformed monitor helped a hunched woman back to her seat.

Meticulously coifed hedges, with not a branch out of place, lined

the fairgrounds' perimeter. Closely cropped

grass extended as far as she could see, like a green carpet; Mrs.

Jackson couldn't smell pollen or the pungent

aroma of fresh lawn clippings. The day was just right.

"Yes, they planned well, thought of

everything," Mrs. Jackson approved.

"I never expected refreshments or seating. At

least we'll be comfortable, even if the

line's bad."

A scrawny man, just ahead of the couple in line, rotated his

chair to face them.

"You think this line's bad? You should have been here at 5 AM,"

he grunted. "We're the last stragglers. One of the caterers told

me that people started arriving before midnight; by 5 AM, the

line was four miles long and spiraled around the tents eleven

times. But, at least the Paradise staff was prepared. The

monitors were already out here, offering people chairs and

handing out blankets to anyone who wanted to sleep." He paused

and glanced down apologetically. "Sorry for not

introducing myself; you'd think that I left my

manners back in the office when I retired. I'm

Dan. Glad to meet you, it's always good to

meet someone in the line to Paradise."

The hostess stopped her cart beside a plump woman who offered to

show her pictures of the grandchildren; she examined the frayed

photos and praised each. The grandchildren were all so beautiful

and charming, had faces that could be on TV, obviously made

Grandma proud; the hostess sang out her praises rhythmically, as

though energetically reciting a mantra. Mrs. Jackson unzipped her

purse; the snapshots of her own grandchildren, tea stained and

years out of date, lay at the bottom of the bag, under the pill

jars, brush, comb, compact mirror and pounds of spare change. Mr.

Jackson wedged his hand into his pocket, feeling for the wallet

where he stored his driving license, social security card, family

photos and other valuable documents in plastic compartments.

"They didn't need to call in police reinforcements until 10, when

the place opened for business," the round-faced grandmother

suddenly trilled. Finished with displaying her photos,

she'd swiveled her chair to face the Jacksons;

she drank her lemonade quickly and relaxed into her cushions. "A

few people tried to cut through the tent, unsuccessfully because

the fabric's so strong, but most people waited

patiently through the night and early morning. Napped, played

cards with the people near them, embroidered, wrote letters; all

peaceful and quiet, what you'd expect from a

bunch without much fuel left in them."

The woman pushed down the white corner of a snapshot that poked

up above a rim of fabric, then patted her pocket to be sure that

all her grandchildren were safely in place.

"But, when the flaps opened,"

she continued, "A crowd stampeded forward.

Rushed, as much as they could rush. Maybe only 25 or 30

troublemakers, but twenty-five's enough to

bring in the cops. I don't know where those

folk found the energy, they must have ignored their bad tickers

and all the doctors' warnings. An amputee got

pushed to the ground; one man charged at the ambulance crew with

his wife's knitting needles when they cut in

front of him. A woman from far back in the line stormed away,

then tried to ram her car through the side of the tent fifteen

minutes later. She sat very low in the driver's seat, her head

barely visible through the side window; a man fainted when the

hell-car sped forward, seemingly driven by its own

will."

Mr. Jackson, noticing that the plump lady wore sunglasses, rubbed

his own eyes, which teared in bright light.

"Typical crowd behavior," he sighed, then turned to his wife.

"The tent makes sense - easy to put up and

take down. How many people do you think it holds?"

Mrs. Jackson shrugged.

"It could hold several football stadiums," Dan replied.

"That's what? - thirty

thousand people? A hundred thousand? Four, maybe six, miles of

people have snaked their way in."

"And no one's come out," the round-faced woman added.

"No one's left," Dan agreed. "We'd see them. That dark opening at

the far left, that's the exit. But no one's come through there,

not even a janitor."

Mr. Jackson didn't ask the man how he'd distinguish an exiting

customer from a janitor. He didn't ask why

none of the shoppers had left yet; the bargain hunters would be

trapped inside by their own greed. Instead, he drew circles in

the air with the toe of his raised shoe and tried to resign

himself to waiting. Mrs. Jackson shifted the heavy purse on her

lap from her right thigh to the left, then back to the right; the

mounds of coins clinked as they thudded from side to side and the

stiff vinyl edges dug into her skin.

"A shame that we didn't bring magazines," Mrs. Jackson said after

a while.

"A shame that we don't have a deck of cards.

Nothing better than a game, penny ante, to help you get rid of

those coins at the bottom of your purse; you

wouldn't have to jingle whenever you move,"

Mr. Jackson replied.

The two folded their arms across their chests and gazed ahead,

vision blurred and thoughts slowing as they made ready for a long

wait.

"No more allowed inside for now, the tent is

full," a monitor, flanked by a burly policeman,

announced into a microphone. "We sincerely

apologize to all of you, who've been waiting

so patiently. We hope to admit many more of you, all of you

eventually, as soon as some shoppers leave. As a consolation

prize, we offer all of you a choice of

free--"

Several from the front of the line stood abruptly and marched

towards the tent; others, limping and shuffling behind them,

yammered protests.

"Stand back!" The cop barked and

blew his whistle "Wait here or come back in

three hours!" Seeing that the old people

wouldn't obey, he retreated a step and

frantically beckoned to his fellow officers. Five policemen

silently moved into guard position between the crowd and the

tent. A German Shepherd bounded towards the entrance, its taut

muscles rippling; a cop gasped to keep up, gripping the leash in

one fist while clutching at the holstered gun that his jiggling

belly threatened to dislodge.

"Three hours!"

"You keep us waiting all this time, and then

you turn us away?"

"And in this hot sun! It may seem balmy to

you, but 'balmy' becomes hot

when you wait and get nothing!"

"I thought this operation was organized.

What's with you people?"

Many in the crowd grumbled and muttered reedy curses: Damn

them, they can't just toss us out like bags of

rotting old garbage! But what can we expect,

isn't it always like this for us, the

dispensable ones, the faceless leftovers? Some hissed; the

most energetic hollered. A woman shrieked and hurled a bottle of

Aspirin at the policeman; another kicked him with the

steel-reinforced instep of her orthopedic shoe and scratched at

his face with brittle nails. A whistle screeched; a dropped radio

crackled static under pounding heels. As more police rushed

forward, old men brandished metal walkers and swung their canes.

"Who are the old farts now?" a

raspy tenor yelled. "You're

the old farts - full of hot air promises!

Chasing us away after we've stood here all

this time. And with our heart conditions and asthma? How fair is

that, you good-for-nothing windbags, to let us risk our health

and then get nothing in return"

"You'll get in, just a

little later. Lets not start a riot here, a little extra time in

line isn't worth a riot," the

monitor intoned in a velvety baritone.

"We'd let you all in now.

But we can't. It's a matter

of safety codes; regulations limit how many can occupy the tent

at one time, and we have to obey the law." He glanced

nervously at the cop beside him, a lanky redhead this time, then

continued in a slow voice as rich and soothing as molasses.

"I know that regulations

don't mean much when you've

been waiting so long, when you're tired,

disappointed and furious. I've been in your

situation - not for something as big as this,

but for something that was very big for me -

and I felt like ripping the tongue out of the manager who made me

wait: I wanted to skin him alive. So, believe me, I know what

you're feeling. No, we

can't give you back the time

you've lost to waiting. But, perhaps, we can

offer you proof that our apologies are sincere. Our hostesses

stand ready to pour you Champagne, scotch, gin, red wines and

beer; they'll also be serving crab salad and

shrimp cocktails, originally intended for the buffet, to help you

through your hunger. And one of our musicians, a virtuoso

violinist, has agreed to leave the tent and perform especially

for you - any tune, a classical piece or a

love song from your honeymoon days, just ask and

he'll play what you desire."

The angry old people stopped, looked at each other, shrugged and

nodded, and began trudging back to their chairs; drained by their

outburst, they shuffled more slowly and paused more often to lean

into their canes and catch their breath.

"They have a point…about

regulations," one stooped man muttered between gasps

for air. He inhaled deliberately, wheezed out a cough, then wiped

the sweat from his ruddy cheeks. "When I was a

carpenter…everything was

codes….Had to obey the

codes…or get run out of

business."

A plump woman, who still bothered to dye her hair, spoke, then

glanced up at her husband, then continued speaking as she fixed

her gaze on the ground in front of her.

"Champagne's not so

shabby," she reassured. "You have

to admit, they're doing their best to make a

bit of bad luck as pleasant for us as possible. And a violinist

especially for us! Maybe we can get him to play that Italian love

song we liked so much when we were courting; I wish I could

remember the name, but if we hum a few bars,

he'll probably know which song we want. Just

thinking about it takes me back, makes me feel like I could dance

across the floor with my skirt whirling and the pearls swaying

back and forth across my chest."

The husband grunted.

"Violins don't make me

feel young again." His fingers rose to a plastic

button in his right ear.

"Don't hear the high notes

like I used to. But crabmeat -

that's special by itself; how much does it

cost at the store, when they even bother to stock it? I guess the

Paradise people do have something for everyone, even during an

emergency."

The old people sank back into their motorized chairs. Some

chatted with those waiting near them, the first strangers

they'd befriended in years. Some merely closed

their eyes, hoping to absorb energy from the warm, restorative

sunlight.

"Don't let them fool you,

even if they look peaceful now," a cop stationed at

the back of the line warned an officer near him.

"They're like old cats

- a bit slower, but they still have claws and

teeth. Old cats can be cranky and unpredictable. And some of them

don't know they're winded

and creaky until after they've

attacked."

Mrs. Jackson turned to her husband.

"We don't really want to

wait around, do we? It's almost two-thirty;

Mike's coming at three. We

don't want to keep him waiting, do we? Not

when he's going off to college in a week; we

might not see him again for months."

Mr. Jackson shook his head; he, too, would miss his youngest

grandson.

As the couple strolled south, hoping to meet a bus that would

drive them to their car, an inconspicuous man in an attic two

blocks away pushed a button.

"Mission DebtKill complete," he

muttered into a phone as the first flames shot up and shock waves

from the explosion knocked the Simpsons to the ground.

In a room far away, government officials and CEOs heard the

message over a speakerphone and sighed in collective relief. From

this, and thirty other Paradise Emporium sites scattered

throughout the country, the same words were broadcast: Mission

DebtKill complete.

"So, how many do you think we

got?" the director of military operations asked.

"I know that we'll have to

wait for a body count, plus missing person reports where the

remains are too charred to be recognizably human. But, as a best

guess - a few million?"

"Whatever, it's a big

step forward in debt reduction," a CEO asserted.

"Big savings for everyone in the long run.

We'd have to pay out life insurance premiums

anyway, but at least we can bypass all the health insurance

payouts. Not to mention the savings for the Medicare and Social

Security people. Maybe we missed ten or twenty percent of them,

mainly the ones who are ready to die anyway or a few who are too

rich to be lured out by anything - but

they're not the ones who'd

cost us in the future."

The men in that room raised glasses of champagne in a toast to

the success of their plan.

In a hospital near the Elmsbury fairgrounds, Mr. and Mrs. Jackson

winced as ER doctors treated their superficial burns and pulled

metal splinters from their skin. Both remembered only a sudden

roar and a blast of heat.

"You suffered mild concussions,"

the doctor told them. "But

you're both very, very lucky. The explosion

killed everyone in that tent, and most of the people near it; now

there's just a big crater in the ground where

it stood. If you hadn't already walked quite a

distance away, you'd have been killed

too."

"It's on all the news

stations," a nurse fretted. "Maybe

fifty thousand killed in that explosion. And not just here

- also near Atlanta, near Dallas, near San

Francisco. Someone targeted all thirty Paradise Emporium tents;

all the sales were scheduled for today, and all the tents

exploded when they were filled with shoppers. The

government's blaming

terrorists."

Mr. and Mrs. Jackson, the doctor and the nurse gazed solemnly at

one of the televisions mounted in the ER and strained to hear the

reporter over the din. Probable terrorist

attack….We know where the terrorists come from,

even if no one can prove their identity; in a country at war,

everyone knows who the terrorists are….In

outrage, the nation mourns this slaughter of its esteemed

elders.

Mrs. Jackson cringed as she imagined Maxine and Anna hunched over

booths, examining potted saplings and glittering trinkets seconds

before the detonation. Maybe Maxine had tripped in her garden and

been kept away by a limp. Maybe Anna couldn't

start the Junk-mobile, and missed the explosion while waiting for

a mechanic to adjust the carburetor. Maybe an asthma attack had

kept Tom O'Toole home. But, as a lifelong

realist, Mrs. Jackson didn't sustain herself

on hope; she tallied up the odds and guessed at what was

probable. Suddenly, the red patches on her skin felt very raw and

hot.

"I was uneasy about that

emporium," Mr. Jackson stammered as they walked out

of the hospital. "Maybe suspicious for the

wrong reasons. But terrorists bombed the place. Terrorists! I was

right to feel uncomfortable."

Mrs. Jackson nodded.

As they drove past the closed door of Tony's

Foods and the dark windows of Sam's Deli, Mr.

Jackson felt his stomach lurch. He imagined the curmudgeons

picking over fishing reels and examining decks of cards with a

magnifying glass while debating whether or not to buy. At home,

he dialed each number from his list, then listened to jarring

rings or to a gruff voice from the dead asking him to leave a

message.

"It's just you and me

now," Mrs. Jackson said after a long silence at

dinner, as though reading her husband's

thoughts. Both pushed cooling spaghetti listlessly across their

plates, then dumped the uneaten meal in the garbage.

A week later, the town held a memorial for the victims. At the

ceremony, Mr. Jackson learned that one of the curmudgeons, Andy,

had survived; an angina attack on the first had confined him to a

hospital bed.

Two months later, Sam's family moved away and

sold the delicatessen to a fast food franchise. A realtor moved

into the space once occupied by Tony's Foods.

Young people chatted merrily on streets that looked unchanged to

them; they noticed the same shops and the same people as before

the disaster. When they passed the crater at the fairgrounds,

they vaguely recalled that this was the site where many old

people had died. But those old people lacked faces or voices;

they were members of a foreign species, invisible and unheard,

except when they tugged at pockets for a handout or demanded that

a wheelchair be pushed.

"I wish we could move," Mrs.

Jackson sometimes said.

"But where could we go?" Mr.

Jackson replied.

Mr. And Mrs. Jackson forced themselves to shop at the supermarket

with too many brands and too many lights; they forced themselves

to swallow morsels of food that always tasted bland. They made

themselves watch the evening news and sit for dinner at 6 PM,

routines that meant they were still alive and human, even if the

food went uneaten and they stared unhearing at the screen.

Several other old people had survived, but the Jacksons

didn't try to find them. Their joints ached so

much more, possibly due to their new gauntness, and their people

were gone; they needed a good reason, an unavoidable chore,

before they'd go into this new town of the

young. A wan sediment of dust settled over their furniture; the

leaky faucet dripped rhythmically, marking minutes and hours.

Only Andy ever visited; Andy had been coming for years, belonged

to the old life and the old town.

A year later, Mr. and Mrs. Jackson read an ad for the Hall of

Hope, featuring a "funhouse extravaganza

designed for the handicapped; a garden of delights for the deaf,

the blind, the crippled, the cognitively challenged. Only the

handicapped admitted, free of charge due to the generosity of our

sponsors. A one day event only, at the Elmsbury fair grounds

along Route eight."

Mr. Jackson passed the ad to his friend Andy.

"Would you go to this?" he

asked.

Andy read and shrugged listlessly. "Yeah,

maybe, if I was handicapped. Who knows? It's

free, not expensive like those amusement park rides,"

he mumbled. "So, what's to

lose?"

When Mr. and Mrs. Jackson went to the supermarket, they found

that everyone in the checkout line was talking about the Hall of

Hope.

"Makes me almost wish I were

handicapped," a woman with garishly colored curls

twittered. "Who'd miss a

chance to have this kind of fun? And all - for

nothing!"

"If I had any kind of

disability," a portly man asserted,

"I'd be there at dawn with

my handicap-ticket. Even if I had a little disability

- I'd be there with the

doctors' certificates or school records

testifying that I deserve admission. I might have two legs, but

I'm handicapped all the same; this form proves

it - so move over, Buddy, and let me

in!"

"There's that home for

the retarded at the end of my block," another shopper

added. "Those kids - hardly

kids, most of them are in their thirties -

they go to the sheltered workshop every day, then come back to

eat and sleep. There's not much excitement in

their lives; a Hall of Hope funhouse would do those kids good.

And my sister, who's teaches special Ed and

knows about these things, says that there are millions of people

in this country with serious disabilities. Those people need a

little hope."

Simultaneously, Mr. and Mrs. Jackson felt a cold shiver of

premonition tingle through their spines, and glanced at each

other.

"It's just you and me

now, we're alone together in

this," they thought in unison.